Piazza della Signoria

Piazza della Signoria: Everything to Know About Florence’s Central Square

Known as Piazza dei Signori or Piazza del Granduca, Piazza della Signoria is a magnificent open-air museum and the beating heart of medieval Florence. You’ll find timeless marvels like Benvenuto Cellini‘s Perseus, Donatello’s Marzocco, or Pio Fedi’s Abduction of Polissena here. These works transcend their time to immortalize their creators and depict the refined language of art that embodies the values and virtues of the Medici family – the most important and influential family in Florentine history. Monuments that shaped the history of the 1500s, like Palazzo Vecchio or the Loggia della Signoria, come together before the watchful eyes of attentive tourists, reflecting the social and political life of the ancient Duchy.

History of Florence’s Piazza della Signoria

Piazza della Signoria in Florence is one of the city’s oldest places. Besides the history woven into the veins of its marbles and the folds of its bronzes, there’s a buried history unearthed only during excavations in 1974. These findings estimated that this area’s first signs of human activity date back to the Neolithic period.

In Piazza della Signoria stood an essential Roman thermal complex, a fullonica (a launderette for woolen clothes), and a basilica likely built when Christianity began establishing itself on the Italian peninsula. This monument was replaced by the small church of Santa Cecilia, which was later demolished along with the Church of San Romolo, houses, cemeteries, and various architectural elements within the neighborhood, making way for the new city of the 10th century AD.

Around 1268, the internal struggle between the Guelfs and Ghibellines began shaping the square, giving it a face similar to what we can enjoy today. Starting from the late 1300s, Piazza della Signoria was gradually paved, and the construction of the main monuments that still populate it today began: Palazzo della Signoria, the Loggia dei Lanzi, and the Tribunale della Mercanzia.

This square hosted the most critical public ceremonies, including executions, such as that of the friar Girolamo Savonarola, accused of heresy. He was the same friar who, a year earlier, organized the Bonfire of the Vanities in the same square, where hundreds of books and paintings were burned.

With the creation of the Uffizi Gallery in the 1500s, Piazza della Signoria gained even greater importance. It took on a new neo-renaissance style during the Restoration period, which we can still admire today.

Piazza della Signoria and Florence’s Most Famous Statues

The figure of the Medici family constantly guided the hands of sculptors, turning the statues in Piazza della Signoria into pieces that celebrate Grand Duke Cosimo I and his powerful family.

Consider the Fountain of Neptune, also known as the Big White, from 1575: an emblem of the maritime power of the Medici family and the main water source in the area during the reign of Grand Duke Cosimo I. Cosimo I recognized the need for a public fountain for hygiene and health reasons, and this fountain also became an opportunity for self-celebration.

The fountain’s design was entrusted to Bandinelli, who was assisted by Vasari, Benvenuto Cellini, and Ammannati, who succeeded as master builder. The material chosen for Neptune was Carrara white marble, worked inside the Loggia dei Lanzi. Completed in the second half of the 1500s, the fountain is considered an exquisite example of sculptural Mannerism.

Statue of Cosimo I

The Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I, representing the Grand Duke as a politician and leader, was commissioned by his son, Ferdinando I. This is undoubtedly one of Giambologna‘s most famous sculptures. He also created the reliefs on the pedestal: The Election to Duke, The Conquest of Siena, and The Conferral of the Grand Duke Title.

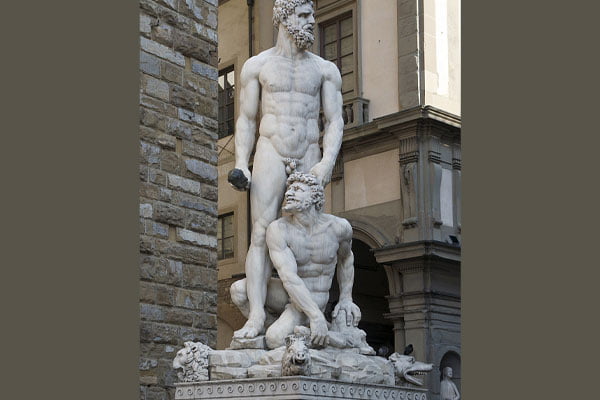

Hercules and Cacus

Hercules and Cacus, forever locked in combat, were sculpted in 1534 by the steady hand of Bandinelli to showcase the unparalleled power of the Medici family.

It was originally commissioned to Michelangelo, who, after sketching the model, abandoned the project, which underwent several changes until it was finally assigned to Bandinelli. Vasari refers to this in his major work, “The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects,” mentioning the deep admiration and constant effort to surpass Michelangelo. Vasari stated that Michelangelo translated Bandinelli’s works into a feeble attempt at imitation, evident even in the sculpture of Hercules and Cacus, which had awkward movements and unnatural muscle dimensions.

Michelangelo’s David

The most famous work of all, Michelangelo’s David, was eventually created to symbolize the values and virtues of Renaissance Florence. It portrays the just man prepared to confront a powerful oppressor, armed with faith in God and the people’s support. Placed in front of the Palazzo della Signoria since 1504, right next to Hercules and Cacus, it has been replaced by a copy and transferred to the Galleria dell’Accademia (Accademia Gallery) in Florence.

The history of this worldwide masterpiece is controversial. Initially commissioned to complete the colossal work for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, it was supposed to be placed on one of the external buttresses. However, the marble posed many problems for the sculptors working on the model. That piece thought to have depicted some vaguely anatomical forms, was of poor quality, fragile, and riddled with holes.

Just as the great artists were about to give up, the young Michelangelo stepped forward. Isolating himself in a workshop, he tirelessly worked on David from November 1501 to 1504. Only on June 23, 1503, did the sculptor allow the public to see his still incomplete work. After careful consideration by the most influential artists of the time, the chosen location for David was Piazza della Signoria. There’s an exciting curiosity about Michelangelo‘s compensation for this extraordinary work – to learn more, we recommend you keep reading!

Donatello‘s Judith and Holofernes, a splendid bronze now housed in the Sala dei Gigli in Palazzo Vecchio, was initially placed in front of the Palazzo della Signoria. David replaced it. After various moves within the square and subsequent museum displays, a faithful copy was placed next to the Big White. Today, it still impresses with its drawn sword towering over the severed head of the usurper – another allegory of Florentine political history.

Donatello’s Marzocco

Donatello’s Marzocco, another symbol of Florence worldwide, was commissioned during Pope Martin V‘s visit to Florence to embellish the staircase leading to the accommodations of the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. Later, it was moved to Piazza della Signoria, becoming a symbol of Florence itself. The particular gray color of this sculpture is due to “pietra serena,” a sandstone highly appreciated in Tuscany at the time. Like Judith, the Marzocco has been replaced by a copy and moved to the Bargello Museum.

The statues within the Loggia della Signoria (loggia dei lanzi) piazza della signoria and their history

Among Florence’s monuments, those inside the loggia tell the transition from the Republic to the Duchy through the stories of their subjects. Exhibited here by the will of Grand Duke Cosimo I, they were carefully selected to express their political significance to the discerning observer, a role performed by Benvenuto Cellini‘s Perseus with the Head of Medusa.

A masterpiece of Florentine goldsmithing, along with the David, Perseus is the main attraction of Piazza della Signoria. The message directed to the population through the killing of Medusa is the end of the poisonous Republic, like the serpents of the Gorgon, which threatened the people’s serenity and democratic principles. An epitome of Mannerist sculpture, it comprises three bronze pieces cast in a complex assembly process that engaged Cellini and his assistants for about six years. It was unveiled to the public in 1554 and placed in the Loggia della Signoria, exactly as Cosimo I had commissioned.

Next to Perseus, you’ll find Flaminio Vacca’s marble Lion, which guards the loggia’s staircase alongside its Roman-era counterpart. Both are guardians of the works housed within this small open-air museum, conceived as such by Grand Duke Cosimo I after the end of the Republic.

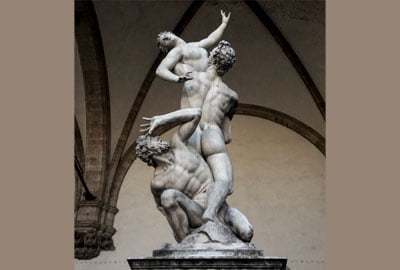

You’ll admire from the square, next to the right lion, Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women: a sculptural group standing four meters tall and displaying unique dynamism, offering various perspectives.

Also known as The Three Ages of Man, the Rape was carved from a single block of marble in a classic style. This was due to a competition that arose between Giambologna and sculptors like Michelangelo, who worked similarly to create his David. The marble of the Rape currently faces significant conservation challenges due to exposure to the elements, likely leading to its display in a museum.

Another masterpiece by Giambologna, located in the Loggia della Signoria, is Hercules and the Centaur Nessus. You’ll appreciate the incredible dynamism of the struggle between the two figures, expressed not only in their poses but also in the tension of their muscles, the expression on their faces, and the veins running through the centaur’s equine body crushed under Hercules’ weight.

This sculpture was moved many times before finding its place in the loggia. Initially exhibited on the Canto dei Carnesecchi, it was later transported to the Uffizi Gallery, near the Ponte Vecchio, and finally to the Loggia della Signoria in 1812.

You won’t be unaffected by the relentless gaze of Neoptolemus, Achilles’ son, who abducted the beautiful Polyxena during the Trojan War. Pio Fedi sculpted his Rape of Polyxena, drawing inspiration from the masterpieces of Bartolini and Canova.

The physical features of the controversial character Neoptolemus, also called “Pyrrhus,” can be traced in the sculpture of Patroclus and Menelaus from Roman art. This sculpture is also located in the Loggia della Signoria. It depicts the King of Sparta supporting the young deceased following his clash with Hector of Troy.

Inside the Loggia della Signoria, you’ll also find Roman-era sculptures of four Sabine women and the princess Thusnelda, a captive of Emperor Tiberius‘ son.

The monuments built in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria

The main square of Florence is surrounded by some of the city’s most important buildings. Foremost among them is the Palazzo Vecchio or Palazzo della Signoria, as covered in the dedicated article: a center of Florentine political power designed by Arnolfo di Cambio, built to accommodate the Priori and later becoming the seat of the commune.

Giovanni Carlo Landi erected the Neo-Renaissance Palazzo delle Assicurazioni Generali during the second half of the 19th century. It stands where the Loggia dei Pisani and the Church of Santa Cecilia were once located to house the Generali insurance company from Trieste. It evokes Renaissance architectural norms in certain aspects. Still, it differs with its pietra serena surface instead of pietra forte, its four-story structure, and arches at its base, revealing its more recent origins.

Loggia della Signoria or dei Lanzi combines Gothic elements with rounded arches typical of classical architecture. Before serving as a museum, it was conceived as an assembly area, a reference point for lords’ festivities and official ceremonies.

Palazzo Uguccioni is a residence commissioned by Giovanni Uguccioni, taking nine years to construct starting from 1550. The facade was likely the work of Marriotto Folfi, while the project was attributed to Michelangelo initially and later to Ammannati or Raphael. This attribution sparked critical interest in this monument, which was previously overlooked and is now protected by the Fine Arts of Florence.

The 14th-century Tribunal of Merchandise, where the Gucci Museum in Florence is now located, was one of the square’s most frequented sites by guilds of the Arts and merchants, often engaged in heated disputes. Their cases were judged here by six foreign lawyers and six councilors of the Major Arts until the Agrarian Assembly of Florence replaced it. You can notice faithful copies of the twenty-one coats of arms of the Florentine Arts on the palace’s facade.

Near Via de’ Calzaiuoli, you’ll find Palazzo dei Buonaguisi, built in the 14th century. It was one of the few buildings not demolished during the road expansion that once bore its name. It features projecting rustication at its base and wide rounded arches beneath ancient medieval shops.

Finally, among the various things to see near Florence’s main square, at the corner of Piazza della Signoria, is the Palazzo dell’Arte dei Mercanti, on which you’ll notice the emblem of the Arte di Calimala – a golden eagle on a red background. Restored in 1383, it also features rustication that stops at the second floor, lower arches, and lintel windows.

Curiosities You Might Not Know About Florence’s Main Square

Piazza della Signoria in Florence is a mosaic of unique curiosities and anecdotes. For example, have you heard of the “chestnuts” on the Equestrian Monument of Cosimo I, the hidden self-portrait of Cellini, or its mysterious fever?

Let’s begin with a gem located two minutes from Piazza della Signoria in Piazza del Mercato Nuovo. The famous Fontana del Porcellino is one of the city’s main attractions. It’s said that rubbing its nose and placing a coin in its mouth brings excellent luck. But beware! The currency must fall beyond the fountain’s grate for it to work.

Via della Ninna, overlooking Piazza della Signoria owes its name to a bas-relief by Cimabue on a wall of the Church of San Piero Scheraggio. Incorporated by Vasari during the construction of the Uffizi Gallery, the work depicted the Virgin Mary put the baby Jesus to sleep, earning it the name “Madonna of the Lullaby” and becoming an object of veneration by the Florentine people.

Only the remains of the Church of San Piero Scheraggio exist today. On them, you’ll find a marble plaque with the inscription: “Remains and vestiges of the Church of San Piero Scheraggio, which gave its name to one of the city’s sixths and within whose walls Dante’s voice resonated in the councils of the people.”

And what about the payment due for Michelangelo’s David in Piazza della Signoria? The young sculptor was reportedly paid four hundred florins.

When the equestrian monument dedicated to Cosimo I was finally shown to the citizens in Florence’s main square, Giambologna hid to listen to public criticisms. After observing the horse for a while, a farmer ecstatically remarked that it seemed almost alive, but something important was missing: the “chestnuts.” These are the characteristic calluses on the animal’s front legs. Upon learning this detail, which he was completely unaware of, Giambologna immediately returned to work and rectified his mistake.

The Florentine coachmen had the bad habit of using the bas-reliefs on the equestrian monument of Cosimo I de’ Medici to hang the reins of their horses. Railings were installed to prevent the artwork from being ruined by such neglect.

Our Top Recommendations

Private Renaissance Walking Tour of Florence with Local Guide

Uffizi Gallery Florence Private Tour with Local Guide

One of the satyrs in the Fountain of Neptune is a copy by the Milanese artist Francesco Pozzi. The original was stolen during the carnival of 1830 by a group of thieves who exploited their disguises as jesters to seize the bronze and camouflage it, thus escaping among the unsuspecting crowd without raising suspicions.

Near the Fountain of Neptune, you’ll find a plaque dedicated to the police, who prevented people from soiling the monument’s water between the 16th and 18th centuries – whether by washing laundry and quills or throwing wood and other waste inside. The penalty was four ducats, and for those unable to pay, the punishment was the “rope’s pull” torture.

The Loggia dei Lanzi, originally called Loggia della Signoria or dell’Orcagna takes its name from the bodyguard of Alessandro the Moor, formed by Lanzichenecchi mercenaries, who often practiced archery here. Indeed, you can observe the marks left by their shots on the right wall, including a more modern inscription carved into the hard stone: “imprinted.”

Among the one hundred and sixty lion heads with hooks adorning the loggia, used to hold tapestries during festivities and celebrations, you’ll find three human heads: a woman, a man, and a child. The reason this small family was carved remains a mystery to this day.

Observing Perseus’ shoulders, you’ll notice something very distinctive: the helmet of the Greek hero and the hair form a stylized self-portrait of Benvenuto Cellini.

The water tank beneath the Loggia dei Lanzi safely stored artworks during World War II.

We want to point out once again the sculpted face by Michelangelo Buonarroti on a wall of the Palazzo Vecchio, visible only from Piazza della Signoria.

It’s said that Cellini assembled his Perseus while suffering from a mysterious fever that weakened him to the point of slowing down his work. He likely fell victim to the so-called “foundry fever,” caused by inhaling toxic fumes emitted by metals during their fusion.

Also, you’ll find a sundial in Piazza della Signoria, specifically on Palazzo Guidacci. This rectangular one was constructed during the 19th century and indicates noon.

Piazza della Signoria: Opening Hours and Ticket Prices

Visiting Piazza della Signoria and the Loggia dei Lanzi is completely free. However, if you want to delve deeper into its history, various tours with expert guides are available, including the Renaissance and medieval city walking tours.

This extensive walk starts in the San Lorenzo district, where you can admire the Basilica and the Medici Chapels, and leads straight to Piazza del Duomo. From there, by proceeding through Piazza del Mercato Nuovo, you’ll reach Piazza della Signoria.

From here, you can decide to continue towards the Ponte Vecchio, through which you can reach Palazzo Pitti and the medieval districts of Florence.

Where is piazza della signoria Florence and How to Reach ?

You can reach Piazza della Signoria from Santa Maria Novella station in a fifteen-minute walk. We always recommend moving within the historic center of Florence by foot since a considerable part of the area is pedestrian or bike – eco-friendly and quick!

After passing through Station Square, you must reach Piazza dell’Unità d’Italia on the left and continue along Via Panzani. Turning slightly to the left, you’ll find yourself on Via de’ Cerretani, then on the right, you’ll have Piazza di Santa Maria Maggiore. Once there, continue on Via de’ Vecchietti, turn left onto Via degli Strozzi, then head right to Piazza della Repubblica. From here, turn left and take Via Calimala on the right, go left again onto Via Porta Rossa, right onto Via dei Calzaiuoli, and finally, on the left, you’ll reach Piazza della Signoria.